:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Drawing Sacred Well Water,

O-Mizutori, Omizutori, お水取り

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Omizutori, officially called the Shuni-e,

is a water-drawing ritual held from late February through mid-March at the Nigatsudo hall of Tôdai-ji Temple. Focusing on the hall's principal icon of worship, a sculptural image of Eleven-Headed Kannon, this rite of repentance (J. keka) aims to purge past sins, as well as bring good fortune and protection from natural disasters. What is unique about Omizutori is its remarkable unbroken history: it has been held annually since the Nara period, for over 1250 consecutive years.

東大寺二月堂の「お水取り」は、正しくは修二会(しゅにえ)といい、十一面観音に悔過(けか)をする行法です。 悔過とは、過ちを懺悔して除災招福を祈ること。

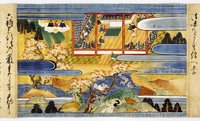

二月堂縁起絵巻(にがつどうえんぎえまき)

Scroll with the History of Nigatsu-Do

二月堂曼荼羅(にがつどうまんだら)

Nigatsu-Do Mandala

二月堂お水取り絵巻(にがつどうおみずとりえまき)

Nigatsu-Do Scroll of the Ceremony

Copyright 2006 , Nara National Museum, Japan.

.................................................................................

quote

Omizutori (お水取り),

or the annual, sacred Water-Drawing festival, is a Japanese Buddhist festival that takes place in the Nigatsu-dō of Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan. The festival is the final rite in observance of the two week-long Shuni-e ceremony. This ceremony is to cleanse the people of their sins as well as to usher in the spring of the New Year.

Once the Omizutori is completed, the cherry blossoms have started blooming and spring has arrived.

© More in the WIKIPEDIA !

. . . CLICK here for Photos !

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

............................ HAIKU

The following are all kigo for mid-spring.

Some saijiki list them as kigo for the New Year, since the water is conceived as some form of "First drawing of Well Water (wakamizu 若水).

Drawing holy water, O-Mizutori お水取り

well of Wakasa, Wakasa no i, Wakasa-I 若狭の井

Monks special training, Shuuni-E 修二会

Ceremony at the Hall Nigatsu-Do, nigatsudoo no okonai 二月堂の行

pine torches, taimatsu, o-taimatsu お松明

The festival is known for the torch lighting and drawing of holy water at a special well. Large torches of pine are carried over the balcony of the temple hall and the sparks fall on the people standing below. If the sparks hit you, it means good luck and health for the coming year.

After this festival, the people of Nara say, spring will now come for sure.

Another event on March 2 is related to the Water Drawing at Nigatsudo. This is the

Sending off Water from the Temple Jinguji 神宮寺,

Obama (in Wakasa) to the Nigatsudo, o mizu okuri お水送り

.................................................................................

U-no-se (鵜の瀬)" River Unose

at the night after Omizuokuri ceremony (お水送り), March 2.

It is believed that the pair of Kami (Wakasahiko 若狭彦 and Wakasahime 若狭姫), who are divinized in the ceremony, descended here.

The Divine Wakasa Wedding

Wakasahiko Jinja (若狭彦神社)

Wakasahime Jinja (若狭姫神社)

. Hikohohodemi-no-mikoto (彦火火出見尊) .

and

Toyotama-hime (豊玉姫).

Look at more of his photos here

- Photos shared by Taisaku Nogi

Joys of Japan, March 2012

You will understand the connection by reading the following report. It is a bit long, but gives a good summary of the ancient events.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Essay by LAURENCE CAILLET

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group

... the time of the festival of the water of youth, a rite which is generally known as Omizutori (the drawing of water) and whose observance is traditionally believed necessary to bring about the return of spring. The best description of the meaning of Omizutori is found in a haiku by the poet Riota (1718-1787):

Drawing of water!

The water of whirlpools warms

From this day also.

Every year since the eighth century the festival has been celebrated at the Buddhist monastery of Todaiji, at Nara, an ancient capital of Japan. Today it takes place in the first and second weeks of March, at a time corresponding to the second moon of the old calendar.

In the Pavilion of the Second Moon, a vast wooden building on the top of a hill to the east of the monastery, twelve monks meet to honour Kannon, the bodhisattva of infinite compassion and mercy. Guided by giant torches whose embers are collected by the faithful as talismans, they return to the pavilion fifteen nights in succession. They walk around the altar, tirelessly intoning hymns of praise and penitence. From the prayer room, which is separated from the holy of holies by a long veil of transparent linen, the pilgrims can see the outsize shadows of the monks praying for the peace and prosperity of the world.

On each of the fifteen days of ritual, six services are celebrated at specific moments of the day and night. Through ten or more hours of incantation to Kannon, of chanting and ritual kneeling, the participants seek to expiate sins committed the previous year and to accumulate merit.

The thousand circumambulations

Almost every night, special ceremonies are held as part of the penitential rites. According to the "Illustrated History of the Origins of the Pavilion of the Second Moon", the oldest manuscript of which dates from the sixteenth century, a Todaiji monk named Jitchu celebrated the feast of the drawing of water for the first time in 752. When he reached the paradise of the bodhisattvas, Jitchu contemplated their ceremonies and asked how they could be imitated and performed by men. The bodhisattvas replied as follows:

"A day and a night here correspond to 400 human years. And so it is all the more difficult, in the short human time-span, to perform the rites according to the rules and to carry out the thousand circumambulations solemnly, without overlooking any detail. Furthermore, how could men reproduce these rites without a Kannon with a living body?"

Jitchu then said: "The ceremony must be speeded up and the thousand circumambulations performed at a run. . . . If I call on him with a sincere heart, why should a Kannon with a living body not come?" And he returned to transmit these rites to men.

Because of the difference between human time and godly time, the monks run a strange race around the altar dedicated to Kannon on the last three days of each of the two weeks of ritual. At first the monks walk very slowly, rolling up the sleeves of their robes and their stoles; then they fasten the lower parts of their garments to their legs. Meanwhile, the curtain concealing the holy of holies is lifted so that the crowd of pilgrims suddenly sees the splendour of the rites and experiences a joy equal to that felt by Jitchu when he reached paradise. Bells are loudly rung during this part of the ceremony.

Suddenly all noise ceases, and in the astonishing silence that follows, all the monks begin to run barefoot around the altar. One of them abruptly leaves the group and rushes into the antechamber of the prayer room where a wooden board known as the plank of prostration is fixed parallel to the floor by a kind of spring. He leaps onto the plank, striking it energetically with his knee, and then returns to his place.

Each time the monks go around the altar, one of them runs and strikes the plank with his knee, the part of the body which symbolizes the forehead, elbow and knees, with which the worshippers must touch the ground as a sign of penitence. Eventually the pace slackens, the curtain falls, the intonation starts again, and the silhouettes of the monks are only visible as grey shadows.

On other evenings, the gods themselves come and dance, disguised as eight monks whose faces are masked by their hair. The first to arrive is the water divinity, who skips and runs with tiny steps and sprinkles the prayer room with lustral water. Next come the god of fire, who scatters embers, and the god Keshi, who sprinkles grains of rice cracked in the fire. Everyone dances and leaps to the noisy rhythm made by three other gods with a rattle, a conch shell and a bell. Two more brandish a sabre and a willow rod to drive away evil spirits.

The well of the god Onyu 遠敷

During these nights of dancing the water of youth is drawn and distributed to the pilgrims. What is the origin of this ritual? The "Illustrated History of the Origins of the Pavilion of the Second Moon" records how "In the province of Wakasa, Onyu, a god who possessed the river Onyu 遠敷川, lingered while out fishing and arrived late at the rites of the twice seven days and seven nights. Profoundly regretful, the god said to Jitchu the monk that as a sign of contrition he would make the lustral water spring near to the place of the feast, and at that very moment two cormorants, one black and the other white, suddenly rose from the rock and perched on a nearby tree. From the traces of these birds sprang water of incomparable sweetness. Stones were laid there and it became the spring of lustral water, aka-i. . ."

And so, on the second day of March, the priests of the sanctuary of Onyu pour into the river a phial of lustral water which is supposed to flow through an underground channel and reach the spring of the Pavilion of the Second Moon during the night of the twelfth to the thirteenth. (U no Se in Wakasa, see photo below.)

On that night, at two o'clock in the morning, the "master of esoteric rites", wearing a brocade hat, leaves the pavilion and turns towards the hill where the miraculous spring is located. With him is a faithful layman wearing a hermit's white robe. He is followed by monks bearing magic rods to which conch shells and bells are fastened. The conch shells are sounded and then, guided by a lay torch-bearer, everyone goes down the steps leading to the spring. At that moment, an orchestra begins to play ancient Chinese music and the monks pray for the water to gush out.

Today the spring (Wakasa no I 若狭井) is concealed beneath a flimsy building with a grey-tiled roof, the four corners of which are adorned with birds. Some think the birds are pigeons, others that they are messenger cormorants of Onyu, the god of fishing and sovereign of the waters which according to Japanese beliefs form a reservoir of longevity, if not of eternity. He is also associated with cinnabar, the essential component of the elixir of immortality which the Taoists of China and Japan tried to concoct in ancient times.

Only the hermit and the master of the esoteric rites enter the building which covers the spring. The water, carried three times in buckets to the Pavilion of the Second Moon, is poured into a wide tub of light-coloured wood which is immediately covered with a white cloth and offered to Kannon. From that day on it is distributed to the thousands of pilgrims who flock to receive in the palms of their hands a few drops of this extraordinary liquid which encourages longevity and is a panacea for all ills.

In spite of its extreme solemnity, this rite is not very different from that with which peasant families welcome the spring. On the eve of the first day of spring, the master of the house, his eldest son or a specially chosen servant rises while it is still dark. He dons a traditional kimono and bows before the altar of the household gods after sprinkling himself with a few drops of purifying water. Then he puts on new straw sandals and goes to the nearest spring. Beside the spring or on the lip of the well, he offers the water-god rice cakes and, while reciting a magic formula, draws with a new ladle and bucket the first water of the year.

Without speaking to the people he meets on his way, he returns home and places the freshly drawn water on the household altars. Then he awakens the members of the family and each one drinks tea brewed with this water of youth which as far as possible compensates for the aging caused by the New Year. According to tradition, people become a year older at New Year, not on their birthday.

The origin of this marvellous water is described in the following story from the southern island of Miyako: "Once, long ago, when men settled on the beautiful island of Miyako, the Sun and Moon wished to give them an elixir of immortality and sent them Akariyazagama, a young servant with red hair and a red face. On the night that marked the changing of the season, Akariyazagama came down to Earth with two buckets, one of which contained the water of immortality and the other the water of mortality.

The Moon and the Sun had ordered him to bathe men with the water of immortality and to bathe the snake with the water of death. As Akariyazagama, tired after his long journey, put down the buckets beside the road and urinated, a great snake appeared and bathed in the water of immortality. Weeping, Akariyazagama had men take a bath of death and then returned to heaven. When he described how he had carried out his mission, the Sun was furious and said to him: `Your offence against men is irreparable. . .'

"Since then, the snake is reborn when it sheds its skin, whereas men die. However, the gods took pity on men and wished to enable them, if not to live for ever, at least to grow somewhat younger. And so each year, on the night before the day of the feast of the new season, they send from heaven the water of youth. That is why even now, at dawn on the day of the feast of the first season, water of youth is drawn from the well and all the family bathes in it."

The water of youth which rises at the foot of the Pavilion of the Second Moon (Nigatsu-Do), like that which bubbles up in family wells, thus comes from the other world. It is carried by waves from the distant land of the gods, the land of Tokoyo, a world both sombre and luminous, a land of abundance and immortality, but also the resting place of the dead on the other side of the sea.

Penitence and the absorption of holy water are two facets of a single hopeless desire to obliterate the wear and tear of time and establish in the world of men something of the eternity which is the prerogative of the gods.

http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1310/is_1989_Dec/ai_8279355

U no Se in Wakasa, where the water is drawn.

若狭の鵜の瀬 Unose

. Tokoyo no Kuni 常世国, 常世の国 The Eternal Land .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

source : uramoto-omizutori

Nigatsudoo ni komorite 二月堂に籠もりて

In retreat at the Nigatsu-Do Hall

水取りや氷の僧の沓の音

水取りや籠りの僧の沓の音

みずとりや こおりのそうの くつのおと

mizutori ya koori no soo no kutsu no oto

Water Drawing Ceremony !

the sound of wooden clogs

of the freezing monks in retreat

Tr. Gabi Greve

This is a most famous haiku by Basho in his Nozarashi collection.

The spelling of koori 籠り is often given with the Chinese character for "freezing" 氷, making it "freezing monks". It is a pun playing with both meanings.

The large wooden clogs for the priests and monks make a rather special noise when they all walk along the stone paths or the wooden floors of the hall.

. Matsuo Basho 松尾芭蕉 - Nozarashi Kiko .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Onyuugun 遠敷郡(おにゅうぐん)

by Taisaku Nogi:

Some people believe that Onyu (遠敷), where Wakasahiko jinja is located, was originally お丹生, and that Omizuokuri/Omizutori ritual is

a metaphor of sending mercury to Nara.

Actually at Omizuokuri ritual, I saw lots of red stuffs, metaphor of cinnabar - Akasui (閼伽水), Akaido (閼伽井戸), red cross, fire, reddish soil's cake, etc....

Niutsuhime - 丹生都比女 Cinnabar and Mountain Cults, by Gabi Greve

Kannon Bosatsu by Mark Schumacher

BACK TO the World Kigo Database : Saijiki of Buddhist Events

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

. Temple Todai-Ji 東大寺 .

. WKD : Festivals from Nara Prefecture .

[ . BACK to DARUMA MUSEUM TOP . ]

[ . BACK to WORLDKIGO . TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

4 comments:

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

若水 Wakamizu, the First Water as kigo for haiku

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Nara torch ceremony heralds arrival of spring

An annual torch ceremony has begun at Todaiji Temple in the ancient Japanese capital of Nara, signaling the arrival of spring.

Buddhist monks pray for national stability in a ceremony called "Omizutori," which dates back to the 8th century.

In the main ritual, called "Otaimatsu," on Thursday evening, 10 monks climbed the long stone stairs to the temple's hall. They were guided by 6-meter-long torches weighing about 40 kilograms each.

Their assistants waved the torches and scattered sparks from the hall's balustrades over the spectators below. People cheered as they believe exposure to the sparks keeps them healthy during the coming year.

One visitor said he prayed for everyone's happiness, especially in light of the March 11th earthquake and tsunami in the country's northeast last year.

The ritual takes place each night for the next 2 weeks.

NHK NEWS

http://www3.nhk.or.jp/daily/english/20120302_01.html

.

"Oikemono Jinji (オイケモノ神事)" at

Kamo Jinja Kamisha (加茂神社上社))

in Wakasa, Fukui.

http://japanshrinestemples.blogspot.jp/2013/02/wakasa-kamo-jinja.html

風神としての天狗 Tengu as God of the Wind

During the 奈良の水取 Mizutori ritual in Nara the Tengu from all of Japan come here and produce a cold wind.

.

Wind God Legends

http://heianperiodjapan.blogspot.jp/2015/08/fujin-wind-god-legends.html

.

Post a Comment